For many people, and especially neurodivergent people, communication is a life-long struggle that– no matter how much we practice and adjust– rarely seems to go the way we expect.

Regardless of how careful we are to frame what we say, there is a strong chance that it will be misinterpreted. Sometimes, misinterpretations are catastrophic and can cause fractured friendships, job loss, marriage dissolution, arrests, or other life-altering negative consequences.

Usually, though, those communication differences are the proverbial death of a thousand paper cuts, resulting in an existence of never being able to communicate casually. Every communication is thought about and over-thought. Life is spent walking on eggshells. We either stop telling jokes and accessing our humor or face more rejection. We stop talking about our passions, or we risk people feeling bored and disconnected.

If our communication style is the minority way of communicating, then how we inherently need to relate to others is pathologized as being wrong and a deficiency. From that angle, there is nothing that we can do other than to apologize in perpetuity and interact in a way that others deem broken, disordered, and lacking. We are told that we lack empathy, we lack interrelational intuition, and we lack social skills. No one is expected to accommodate our communication styles, so all the work is on us to constantly override what comes naturally.

But we know that autistic people do communicate differently and in ways that make sense to other autistic people. This is not to say that every autistic person seamlessly communicates with other autistic people, but we do communicate with each other much more fluently than others communicate with us. Our instincts do not fail us as often.

A Minority Within the Minority

But even within the autistic community, there seems to be at least two distinct communication styles that account for a lot of miscommunication. The same difficulties I have had with non-autistic people often happen within the autistic community. It seems that without understanding these communication differences, the potential for conflict is high.

Concluders and Weavers

I would like to posit that there are two types of communicators that exist within the autistic community. While there may be more, these are the two that I have been able to identify. These may not be exclusive to autistic people, either, and may also correlate with other forms of neurodivergence (ADHD, dyslexia, Tourette’s, etc.).

Concluders

Concluders are, by a large margin, the majority of communicators. I’m calling them “Concluders” because they speak with the intention to make a point. They may speak directly:

This person is “blunt,” and they do little padding of their communication with platitudes, examples, details, metaphors, or flowery language. Others are less direct:

These people are still Concluders, but they may speak indirectly and pepper their communication with lots of hints and tangents. Others take the scenic route:

These communicators are effusive storytellers. They have metaphors and analogies, use lots of words, might be distractable, and are known as “talkative,” but they still have a destination, or a “point” they are trying to make.

And you may be thinking… “Isn’t there always a point?”

Yes, and no. I’ll Explain.

Enter Weavers

Weavers are a small minority of communicators, and they do not communicate with a destination in mind. That is not to say that they don’t have a “point,” per se, but they don’t have a defined destination. They are not, generally, communicating to make a point. They are looking, instead, to make a tapestry. Weaver communication, using the same map as above, is more like this:

When Weavers communicate, their conversations are to build a dimensional pattern with many “points” that are intended to intersect with their conversational partners points. Weavers do this by stating facts. This confuses Concluders because it appears that they have reached the end of the conversation or the “point” without expecting any input from them.

Concluders often wonder of Weaver communication, “What’s the point?” Weavers have probably been asked that very question many times in their lives.

Because people only think of communicators as Concluders, they apply the same rules of Concluder interaction to Weavers. They don’t do this intentionally, of course, because they are not aware that some people are Weavers.

Weavers throw out a fact, though, hoping that their conversational partner will respond with another fact. This fact isn’t meant to be an end point, but an anchor point for the other person to toss out there intersecting fact. These facts aren’t endpoints at all. In fact, Weavers don’t typically make end points.

When a Weaver throws out a fact, it’s intended to be more like an open-ended question that asks, “What does your thing have to do with my thing?” or “What experience do you have that is like my experience?”

I have documented this before in my article, Very Grand Emotions, and have seen other Autistic people opining on the same conversational dilemma. For Autistic people who are weavers, their communication style is painted as having a lack of empathy because they respond the way that another Weaver would respond.

This tendency has been catastrophically described by Simon Baron-Cohen as being “mind blind” or not knowing how to empathize. This couldn’t be less true, though. Weavers have profound empathy, which is why they are responding in a way that other Weavers would find validating.

Deeper Than Conversational Differences

Weaver communication is more than just being wired to respond with a counter-point or another pin in the map of human experience. Weavers have different expectations of relationships that are grounded in a set of values about what communication means. These values are as innate and intuitive as the conversational norms of Concluders.

For a Weaver, communication exists to build this dimensional pattern that intermingles one person’s world with the other based on what the other person wants to share. The foundation of this style of relating is that the other person’s input is not based in guided discussion with a destination in mind (like Concluders) but on allowing the other person to choose the pattern they will form.

Weaver communication is like a dance that allows for a regular trade-off of who is leading and who is following. Unfortunately, when trying to dance with a Concluder, the result will be a lot of toes being stepped on. Concluders believe that this exchange of facts is just someone trying to be dominant because they don’t understand the “point.”

Here is a conversation that I had with someone whom I knew had many conflicting beliefs and values. I let him know that I was difficult to offend. Here’s how the conversation progressed:

Him: good; we’re two thick-skinned folks

Me: Yes, haha. One of my favorite quotes is from Moby Dick. The blacksmith tells Ahab, “Not easily can’st thou scorch a scar.”

At this point, a Concluder would have probably just glossed over the quote. But, I knew I was speaking to another Weaver when he responded, (some lines removed to protect confidentiality. Conversation shared with permission):

Him: Gibran also poses: “Out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls; the most massive characters are seared with scars.”

Me: Well played

Me: So you’re autistic, too, is what you’re telling me, haha

Him: someone just asked me if I were

Him: I carry no diagnosis

Him: [although Leondard Cohen is the best]

Him: “Children show scars like medals. Lovers use them as a secret to reveal. A scar is what happens when the word is made flesh.”

This is how two Weavers getting to know each other might interact.

Weavers interact in large part by quoting things that have resonated with them in the past, and those things often are the same things that have resonated with other Weavers. This is, obviously, because they have identified people who communicate the same way in literature, pop culture, film, or historical context.

If someone read through my and my brother’s text messages through the years, they would probably find it utter and complete nonsense. It’s what I’ve come to reference as “Peak Weaver.”

Here’s a snippet from one conversation:

Me: Insipid Manhattan debutantes

Him: Cruel Intentions

Me: No

Him: Best of the Best!!!

Me: I am the son of the woman who replaced your dead mother for a time. It was your anger that drove them apart!

Him: It’s a lie!

Me: It’s not a lie!

Him: Robin Hood. Love that one.

Me: And placed into it not one, but two large pieces of sheep shit

Him: White water in the morning

Me: 60% of the time, it works every time

Him: Is that gasoline I smell

Me: Hey, this alien looks just like a hot guy

Him: Hippa than a hippopotamus

Me: Sprinkle me

Him: I killed a man with a trident

Me: Everlasting strength

Him: Best one yet

Me: [Screenshot of me sending “Everlasting strength” to our cousin about 20 times in a row]

Him: Pete Incaviglia

I suspect that other Weavers will maybe recognize some lines from the above. Others are inside jokes. There are several quotes from Chris Farley, Norm Macdonald, or Will Ferrell movies. The “Hippa than a hippopotamus” line is a reference from an episode of Soul Train we watched in 1995. It’s from a song called “Sprinkle me” by E40.

“Everlasting Strength” is a line from a song that used to haunt my cousin (another weaver). This is probably from 1989. Pete Incaviglia is a baseball player who tripped and fell into a dugout while trying to catch a foul ball– maybe in 1992. The word “No” is a James Earl Jones quote from the movie, Best of the Best (1989). While a billion people have uttered the word “no,” we will know exactly what that means.

The longer Weavers know each other, the more complex their tapestry becomes. This is no different than two people telling stories that begin with “Remember the time when…” It’s simply a different way of being nostalgic and is based on different conversational expectations.

Other times, our conversation is an exchange of quotes from people like Alan Watts, Herman Melville, and recording artists who are probably all autistic Weavers. We have always gravitated to the same things, and the more Weavers I meet, the more I learn that we all tend to share similar interests.

My most powerful relationships have been with other Weavers, probably because we naturally seem to get each other. In fact, without understanding what it means that some people are Weavers, it can feel like the first time that someone else has ever understood us. We feel like we are completing the other person’s brain because, in a way, we are. We are fleshing out the intersecting tapestry that combines our thoughts and experiences with someone else’s.

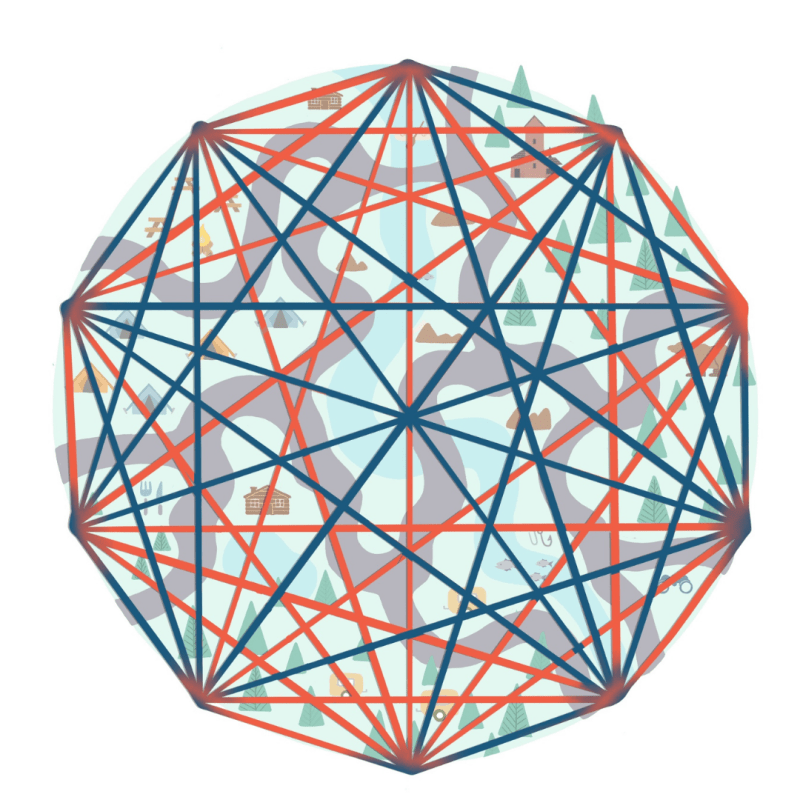

In fact, I named the protagonist of my novel Isaac in what is a very Weaver move (all of the names are Weaver moves). Isaac is named after Icosahedron, or a shape that I think represents Weaver relationships:

All of my closest friends are Weavers. We trade quotes and memes and build on previous “points of contact” so that our tapestry becomes more complex and interwoven. Aspects of this communication are hilarious, other are profoundly emotional.

Weaver Communication is Hard-Wired

I have a theory about Weaver communication and the specific ways that some brains are configured. Weavers tend to be good at memorizing things that resonate with them, like song lyrics, lines from movies or books (sometimes even whole movies), and other large pieces of information.

My daughter is definitely a Weaver. Others have remarked on her memory and how with each person she knows, she will remember little “things” they had as points of interaction that were in some way meaningful. She remembers and brings up things from the past, and I know the response she’s hoping for. She wants them to build on those moments of connection and weave a tapestry of relatedness together.

This doesn’t always pan out for her, though, as others don’t always– or even usually– remember the moment she’s referencing. When I tell them, “Remember two years ago, that time you were throwing rocks in the creek, and you said ‘splash’ with a funny voice and both kept repeating it and laughing at each other?” They think I’m crazy for imagining that a 4.5-year-old could remember something from two years ago or could be referencing that in a conversation years later.

She was a late talker, and our Weaver communication was totally wordless before she began to speak. We had noises we would make, movements we would build from, and other exchanges that may have seemed nonsense to most people. When she started talking, we would take turns naming objects in lists: words that begin with A, hoofed animals, space words, the alphabet (forwards and backwards), counting by 2s, 3s, or 5s, taking turns saying lines from books she loved, etc.

It seems that most Weavers are both Autistic and ADHD… and are often dyslexic, dyspraxic, and/or apraxic, too.

My theory is that they are right-brain language learners. Please dump the notion that the left brain is the logical part of the brain and the right brain is the creative part. That’s simply not true of neuroscience. What is true, though, is that most people receive and express language predominantly from the left hemisphere of the brain, but some autistic people create language from the right.

I believe that these people are Weavers, and they communicate to create patterns rather than to arrive at an end point.

Weaver Communication and Social Consequence

Weavers live a life of missed connections. They are accused of monopolizing communication or of bringing the topic back to themselves. They do, in fact, bring the communication back to the self because they are trying to open the door for the other person to share their insights.

I have looked for a good example that could be universally understood to describe Weaver communication when it hit me the other day that Lulu Is a Rhinoceros, one of the children’s books we are using as a basis for people to help spread autistic acceptance, is a book about a Weaver who is regularly rejected by Concluders…

Lulu is a rhinoceros who communicates like a Weaver– by throwing out a fact. The dogs she interacts with don’t respond as a Weaver would. They respond like Concluders. They believe Lulu has made her point, and they don’t really know what to do with the conversation.

Lulu eventually runs into another Weaver, though, and they take turns stating facts. These facts serve as open-ended questions, and they figure out how they can create a tapestry together. It’s the start of a beautiful friendship that is less about their commonalities and more about how their differences are complementary.

Weavers Rarely Ask Questions

Weavers do not tend to ask many questions outside of seeking factual clarification. This can seem to Concluders to be disinterest in the other person’s life; however, asking questions generates a point on the map the other person may not want in the tapestry they are weaving and may break the pattern they wish to communicate.

Similarly, Weavers may be uncomfortable with questions because they feel compelled to answer them factually instead of how the other person wants them to answer. Even questions like, “How was your day?” or “How did that make you feel” can change the pattern the other person wants to weave as interaction.

If a Weaver wants to know how the other person’s day was, they would instead state something factual about their day. This is highly nuanced communication, but it just appears like selfish and blunt Concluder conversation to Concluders. Here’s how a conversation might go between two Weavers:

Weaver Jo: I stubbed my toe again.

Weaver Alex: I got my tie caught in the paper shredder at work.

Weaver Jo: I poured myself a pot of coffee but forgot the filter.

Weaver Alex: I put the soap on my toothbrush again.

Weaver Jo: You win.

There are lots of things implied here, and there is a lot of unspoken nuance in this interaction. Both people understand the conversational style of the other, both understand that directly talking about their feelings or even validating the other person’s feelings would be too intrusive, and both are finding the common ground of the absurdity of existence. Their emotions are implied. When Jo cedes that Alex is winning, what they really mean is, “Your day was worse than mine. That must be hard for you.”

Here is how that conversation might go with a Concluder:

Weaver Jo: I stubbed my toe again.

Concluder Reese: That must have hurt. Are you okay?

Weaver Jo: I guess. It still hurts a little.

Concluder Reese: Do you need to go to the doctor?

Weaver Jo: I can bend it.

Concluder Reese: So you don’t think it’s broken?

Weaver Jo: It isn’t swollen or bruised.

This conversation might continue awkwardly with the subject being a stubbed toe. Concluder Reese thinks that Jo is trying to arrive at a destination or make a point, and so they are communicating in ways that help Jo get to their destination.

Since there is no destination in Jo’s mind, Reese will likely feel like Jo has some ulterior motive because they are unable to figure out what the “point” is. Reese might wonder if Jo is trying to make the point that they should be neater around the house and not leave things where someone could stub a toe on them.

What Weaver Jo was trying to do was open a conversation. They were asking, “How was your day?” but in the nuanced way of the Weaver. Concluder Reese is responding like a Concluder might respond and probably is confused as to why Jo brought up the toe at all if it’s not broken, bruised, or swollen.

Concluder Reese will not get an opportunity to talk about their day and may think that Weaver Jo is making the conversation about themself. Neither are selfish, they just are wired with different conversational norms. Weaver Jo will feel disappointed that the conversation is bluntly asking about their feelings and if they need to go to the doctor. Concluder Reese will probably feel like Jo doesn’t care about their day.

Concluders will forever look for a point, and since Weavers are averse to making direct points that have an end goal, these conversational missed connections will happen every day, often ending in hurt feelings and devastating misinterpretations.

A NeuroInclusive Story of Concluders and Weavers

Since Lulu Is a Rhinoceros is such an apt example of Concluder and Weaver communication, I made a NeuroInclusive story about it based on the book. This will simplify the long-form in a way that will hopefully be digestible to younger readers and communicators.

A Theory of Two Types of Communicators

This theory is based on my experience and has been colloquially and individually tested over a four-year span. It is not a scientifically-validated theory and has no empirical support. Other than comparing notes with other autistics and even autistic psychologists and researchers, no data exists to substantiate this theory.

These are the basics of Weaver and Concluder communication, and my intention is to write more in depth on these differences in the future.

Further, even if these two communication styles are valid, there could be other communication styles beyond Concluders and Weavers with different communication instincts. Some people may be a little of both, but I expect that most Weavers have learned to translate to Concluder language since Concluders are the vast majority.

This theory is being published with the hopes to start conversations and to see if others find this information relatable and applicable to their lives. It may help to shape and put words on why they have experienced so many missed connections with people about whom they genuinely care.

Please leave your comments if this resonates with you or if you have other ideas.

click here to leave a tip, click here to gift my child, or let me know your thoughts in the comments.

- The Division Between NeuroDiversity Advocates and The Rest of The World - May 11, 2024

- My family’s autism services are working for us, so we will probably lose them - May 24, 2023

- What autistics mean when we say this world is not made for us: How fun activities push autistics into the margins - December 23, 2022

68 Responses

I’m a weaver, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have a point. When I’m trying to convey an idea, I’m trying to convey it in all it’s nuances. What I’m not trying to convey is a judgement or conclusion. I’m trying to convey all the varying points on which my conclusion rests upon or all the points considered when drawing my conclusion. What I’m looking for in return is points I’ve missed or items in which certain points can be considered from another perspective.

I’m a visual thinker. Inside my head concepts are like 3d rotating images or models and it is the entirety of it that forms my opinion on the matter. I’m not trying to convey my opinion. I’m trying to convey the 3d rotating model and discover if I conveyed it accurately if you draw the same conclusion and if not, why?

YES! Me too!!! That’s exactly how I communicate.

I do a similar thing I feel. I like to set the stage for my main point, but what often happens is the other person gets bored or loses track before I can finish. Kind of dissapointing.

“Most people are Concluders.” This is the only part of the article I have an issue with. Perhaps most autistic people are concluders (survey needed?), but I’ve come to believe that the conversations of most NTs are neither-to draw a VERY broad generalization, their conversations are not about communicating or seeking specific information-I believe that a large number of their conversations are simply about “connecting”. “Connecting” is a rather “touchy feely” term, but I’d define is as ascertaining whether the other party is part of one’s “group”, and if so, getting positive “vibes” from “being with” others, either virtually or literally.

I think they mean it’s most people within the scope of the Neurodiverse or just AuADHD.

I wasn’t able to read every comment so this may be redundant – but I needed to say that your hypothesis aligns well with the work of Barry Prizant and Marge Blanc on Natural Language Acquisition and Gestalt Language Processing!

If you have time and interest I’d encourage you to take a look – you seem to be describing what adult relationships and conversation may look like between two Gestalt Language Processors/Weavers vs Analytic Language Processors/Concluders.

Marge and Barry’s research has been more about children and language acquisition – they have been developing neurodiversity working practices in speech therapy for decades. Their framework complements what you’ve outlined here very well, and you may find a wealth of reseach that supports your conclusions here.

Marge Blanc is also accessible if you join the “Natural Language Acquisition Study Group” on Facebook. I’m sure that she and the (neurodiversity affirming) group would be interested in your findings here. Thank you for sharing this with the world.

I have only just come across this article, so feel a little late to the party. But as I was reading this article I was having the exact same thoughts. A weaver reads as if they have GLP traits. Has there been any further research done into this?

“Thanks” to having acquired ME/CFS & a neurological autoimmune disease I no longer have the energy to follow a weaver. Or to do any weaving of my own. And don’t have the energy to even listen to fast paced music for more than a few moments. And sometimes don’t even have the energy to go down the steps to get the mail. And sometimes don’t have the energy to even focus on painting model train and airplane parts and people for more than a few minutes at a time. And sometimes don’t even have the energy to concentrate on reading a full page in a book – which is frustrating when I can remember once upon a time being able to read a novel at a rate of almost 2 pages a minute and retain the content.

Terra Vance : Here is a model. I worked very hard on it.

Concluders : Allow us to demonstrate your model is useful by disagreeing.

Sasha Solita : And now please allow me to express my profound gratitude for this Truthy model through interpretive dance *wiggles fingers and pirouettes* and now please excuse me I need a stress nap after being in a comments section *blows kisses and runs away*

Hello, I’m an autistic french girl and I struggle with something with my comprehension of the weaver way of communication. (I guess I’m a concluder)

I understand the article and find it very interesting, I definitely can understand better some interaction I had in the past with some peers, and it’s really appreciated.

The thing I block on, is most probably connected to a misunderstanding of my part of the beaver communication and I’m very sorry if it seems stupid of me or mean ; I think that I communicate in the way the article is written, but orally. So for me there is not a lot of differences between the way I would write an article and the way I just express myself so I’m understood.

And this is why I’m so confuse, because as you clearly say in the article, you’re a weaver, and show some exemples of communication that are very different than the way you express yourself while writing the article.

So do you feel like a concluder when writing and a weaver in conversation? Is it hard to have that kind of argumentary speech when communication. Do you feel like it’s two differents tasks entirely to express yourself via an article or through conversation?

In my case it’s a continuity and that’s why I’m surprised to see a strong difference in a way to express themself from the same person.

I hope It wasn’t too hard to understand what I mean, english isn’t my birth language and it’s not really clear in my head either so hard to communicate 😅

J’ai tout à fait compris, Romane

You have a gift for communicating complex ideas in a clear and concise manner.

I’m a concluded and my partner is a weaver. Now I’ve read this, I understand more but I still don’t really get it! 😆 help! Are there any articles or information available that help concludes and weavers understand each other better?

This is really fascinating! I’m AuDHD and I’d like to build on your theory (and your suggestion at the end that people might be both) to include Mimics/Hybrids 😀

At first, I linked this to my brother (also AuDHD & dyslexic) and joked about how we are definitely Weavers, and I think Weaver is definitely my natural style. I resonated with Weavers not asking questions, because I find that very difficult, and also not know what I am expected to answer when someone asks me an open question like “How are you?” especially because it feels like 99% of the time they don’t seem to actually want the answer unless is “Good, thanks!”.

Then thought about it a bit more and realised that because I (like many autis, especially women in my experience) heavily socially mimic, I adjust between Weaver and Concluder (and lets face it, NT style) depending on the situation I’m in and the person I’m speaking to. It’s completely subconscious, and I only realised I did it when trying to figure out why starting a conversation with someone (or even making a phone call) is so difficult – but if someone approaches me and starts the conversation, I’m fine. I realised that I needed the other person to go first because otherwise I didn’t know what their communication style and expectations of me were – there was nothing for me to mimic if I were the approacher. So having read this, I reckon some of that unconscious analysis is determining if Weaving is acceptable with this person (usually not, sadly) or what level of Concluder is required/expected of me.

Interesting comment about writing vs talking – for myself, I’d guess that in written communication (barring informal chat chains), you’re expected to have a point – the framework is pretty universal and well established, especially in academic/published work. Writing lets us plan what we’re communicating, go back and make adjustments and really consider tone etc, whereas talking doesn’t. So maybe we can be talking Weavers, but writing Concluders? It’d be really cool to see some analysis on Weaver vs Direct Concluder vs Journey Concluder writing to see who uses the most parenthises as I’d guess Direct Concluders use very few and Journey Concluders/Weavers use the most (look at how many are in my comment :D).

This was really helpful to me, thanks so much. Helps me understand why I love some conversations and feel super frustrated and misunderstood after some others.

This title, ‘Weavers and Concluders,’ immediately caught my eye! It really resonates how communication is a struggle, especially for neurodivergent people.